The First Irish-American I Ever Met

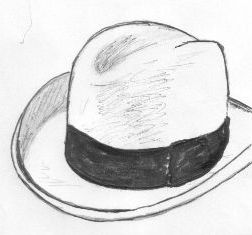

In 1960s Ireland, a cigar-smoking New Yorker in a homborg hat made a big impression

I was about 8 or 9 years of age when I met my first Irish-American. It was the early sixties, when the most important new film to the Irish was “Darby O’ Gill and the Little People”. Sean Connery sang in that movie, and tried to look suave among very short Irish people and harsh-voiced, mean, old leprechaun kings. As he was not yet James Bond, I thought he was a complete twit.

I discovered my Irish-American via the trail of aluminum tubes he left scattered about a farmyard in Thomastown, County Kilkenny, where I worked. “What are these?” I inquired of my boss. “Ah, they’re Uncle Jacks cigar yokes” he replied from under his straw hat and a half-lit Wills Woodbine. (“Yoke” in rural Irish parlance is a catch-all word for what todays Valley Girl would call “thingy.)

Ireland in the sixties was broke, as it had been for the previous 700 years. Our dairy, however, had more modern equipment than most other farms, which were still using simple, open-stall barns. I had to be at the farmhouse each day at milking time. Before long, Jack came out. He never came out unkempt. That struck me as remarkable. A kind of excitement follows the kempt among the unkempt. He was in his healthy seventies, with white hair in a crew-cut style. He always wore a suit. He also wore a homburg hat, like the one I once saw in a Broderick Crawford detective movie. So American. He attended to his appearance, but not in a vain way. I saw this as something America must have taught him.

Jumping Off Bridges

Jack had been born in Ireland, but left for America as a young man. After 50 years in the US, he seemed to me like the quintessential yank. I soon found myself looking forward to his American cadence echoing around the concrete walls of the milking shed that slow, deliberate enunciation. His Irish nephews rapid-fire replies didnt affect his slow, steady voice, which had a timbre of softness and warmth.

Many of the tales he told were very tragic. He had started out in New York during the Depression. “Things were real bad” he said, in such a way as to leave us without any reply at all. On his first day in America, he saw a trucker stop on a bridge, get out, jump into the river and drown. It was so casual an act, so silent, so deliberate. Jack never got over it. Before his first year in the US was out, Jack himself had to be pulled off a bridge by a passerby, who befriended him and helped him find work.

America Of My Imagination

I was awestruck by his tales. His “America” spun around my imagination that whole summer and fall. Oh, the questions I wanted to ask but unwritten rules prevented. Whats Little League? How do you pronounce Connecticut? Did any of your friends go blind in the Bowery from rotgut? What is rotgut? How do you pronounce “precinct”? Were you ever in Precinct 77?

Standing in the frame of the wide milking shed door, he would light his cigar thoroughly, until satisfied he would not have to relight it. The aluminum container I would later pick up for my collection. He watched the milking process with some interest. Every now and then, he looked out to the horizon — not wistfully. That word did not fit this oddly hardboiled, civilized man. He was looking for something to catch his attention; maybe to trigger a thought in his mind before sharing it with us.

Once, he saw three combine harvesters working the wheat in a large field off in the distance. They belonged to a farmer we had nicknamed Watt Towey (we nicknamed everybody in the whole town). Watt had seen this way of harvesting wheat in a book about Canadian farm methods. Very few local farmers could afford to rent a combine Harvester, and Kilkenny farm fields were decidedly not Saskatchewan-sized, so Watts new methods were causing a stir among the locals. Although Jacks nephew was amazed by the big machines, Irish-American Jack looked on it all as very small-scale stuff.

Jack died before the next summer had arrived. Visiting Ireland years later, after emigrating to the US myself, I decided to steal into the farmyard where so much of my youth was spent. There, lying deep in the weeds by the dairy wall was one of Jacks cigar yokes. I lifted it up carefully and rubbed it clean. All the colors and print were long gone, like Jack. But still it was there, like Jack.

Tom Cahill grew up in Kilkenny, and now lives in Texas.